I discovered Yadichinma’s work last December in Dakar, during her artist residency at Maison Aïssa Dione, an annex of the Atiss Dakar gallery, founded by textile designer Aïssa Dione.

Naturally, I arrived late, preferring to wander through Dakar and walk to the residency location. I unfortunately missed the artist’s speech and the exhibition presentation. However, it turned out to be a blessing, as I have a very interesting memory of this residency transcription.

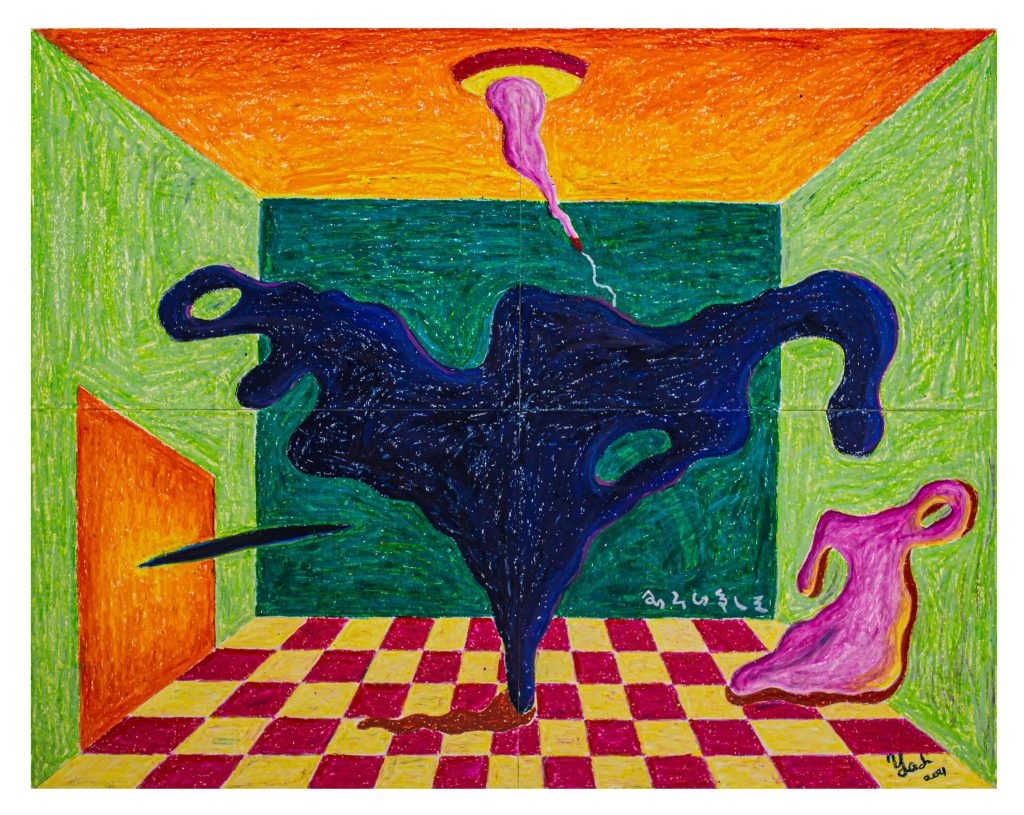

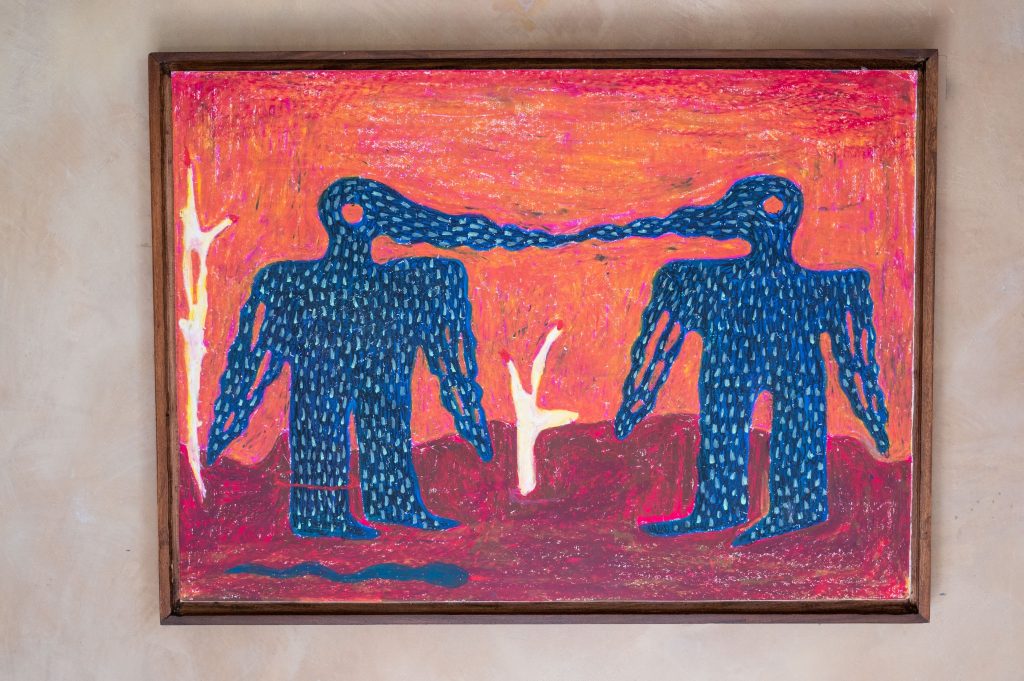

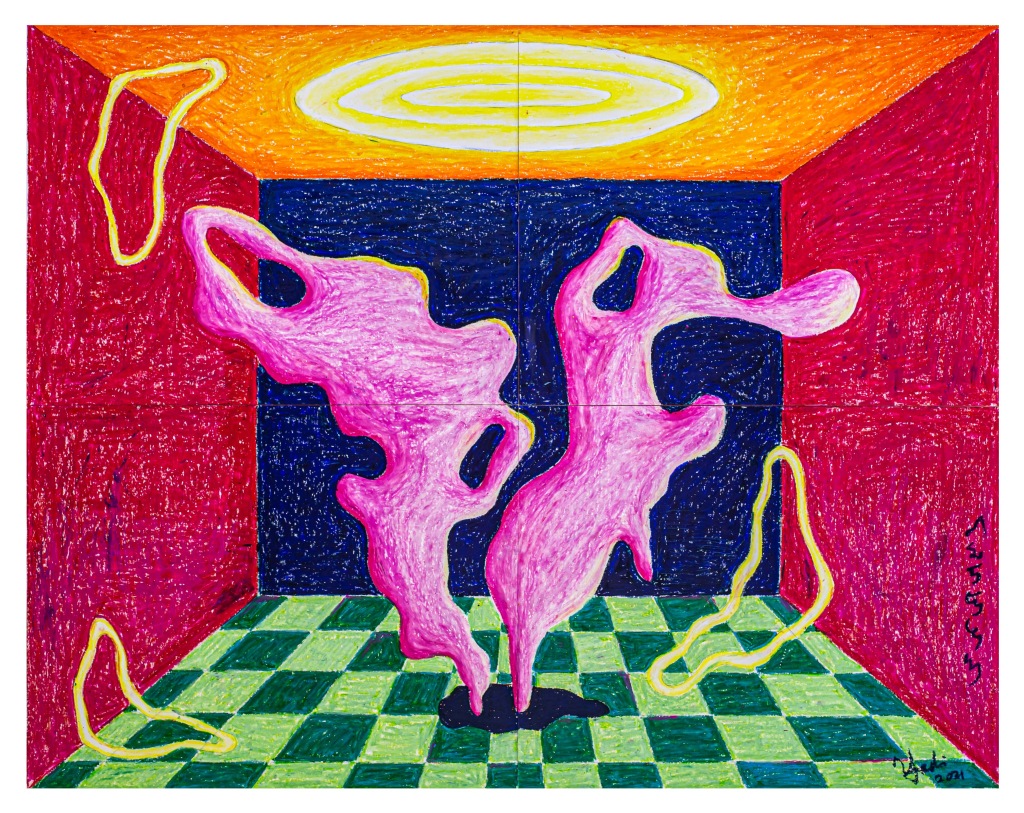

When I saw Yadichinma’s artworks, they immersed me in another universe, filled with abstraction and surrealism. I immediately wanted to learn more about the artist and the message she wanted to convey through these works.

It had been a long time since I had been so deeply moved by such mysterious artworks. I had no key to understanding, but I felt like I was deciphering the works as if they were composed of a universal language.

And what a satisfying feeling it is to be in front of artworks that touch and transport us in this way without needing mediation. This experience reminded me that the absence of mediation could be a blessing and that art does not necessarily require explanation.

I felt a traditional anchoring, which, however, intentionally lacked concrete and apparent foundation. And I also remembered the importance for me of being confronted with artworks by African continent artists.

A few days after visiting Maison Aïssa Dione, I decided to write to Yadichinma to interview her. Full of kindness, she graciously agreed to discuss her work, her position as an artist, and her vision of contemporary art on the African continent.

Yadichinma : I am passionate about documenting African cultures. We have a huge gap in terms of archives, and it is not always easy to access what visual art produced on the continent was and is today. Being a self-taught artist, much of my work and research has been about finding resources and documentation.

AÏKA : Why do you describe yourself as a multimedia artist?

Yadichinma : I describe myself in several ways, and one of them is multidisciplinary which I think means the same thing. I use different techniques and various mediums in my practice. It’s constantly evolving.

I’m very curious about different materials, objects, but I’m also interested in how we, as human beings, interact with them, we form relationships with them. Some objects can be used to create other things; we can almost consider them as their own entities, they have their own meaning.

But yes, the term multimedia comes from the multiple media and different types of processes that I use: I paint, I sculpt, I draw, I create installations. I work with plastic, with textiles, depending on what inspires me at the moment.

AÏKA : Why have you chosen the artistic mediums you currently use? What do they bring to your artistic expression?

Yadichinma : Currently, it’s a bit challenging to keep track of all the mediums I use because there are the main ones; I always have a pencil and paper, for example. One thing I’ve always said about my practice is that I seek, in a way, a primary and elemental approach to creation. I break down processes into lines, shapes, and colors, and following this interest, the easiest way for me to translate an idea has always been pencil on paper. So, that’s a foundation I have throughout my creative process.

Then, plexiglass came about somewhat by chance when I was in residency in Dubai, where I was really looking to see how the city and the availability of the material in that city could affect the work I was doing. There was a laser cutting machine and plexiglass. I thought, “Hmm, there’s something to be done with this material” and I went to get it from a factory and started using it. I later found out that virtually all signage work done in Lagos the city i live in, like the signs that stores have out front, was done with plexiglass.

Nigeria is also a big hub for small businesses. A lot of people use these laser cutting machines and this material, and it’s interesting to think about the language that implies, but also to use it as art.

Another medium I use a lot is soapstone that I discovered about five years ago at the Harmattan workshop in Delta State, Nigeria. It’s a kind of soft stone that can be chiseled and shaped as desired, and I like this process because you can really see the transformation from roughness to what you want. I also really enjoy the physical dimension of the work. Often, the work I appreciate the most is the kind that makes me move and grab things, so sculpting is always very enjoyable.

There is also my textile work where I use fabric and threads. I enjoy this medium because it feels very delicate. There are also so many ways to build fabric, with the awareness that the clothes we wear are made in a certain way. Their cut, their pattern, is a way to embellish them, and so is embroidery. It’s a beautiful way to create images, too; the feeling of the thread on the fabric is really pleasant. It brings a different dimension to drawing on paper because fabric has a texture, and during the process, this texture starts to mean something between your fingers.

I choose my mediums for different reasons, but mostly because they make me feel something. They were created mostly by other artists, and I can add my creative process to the existing material by asking it, ”What can you be today?”

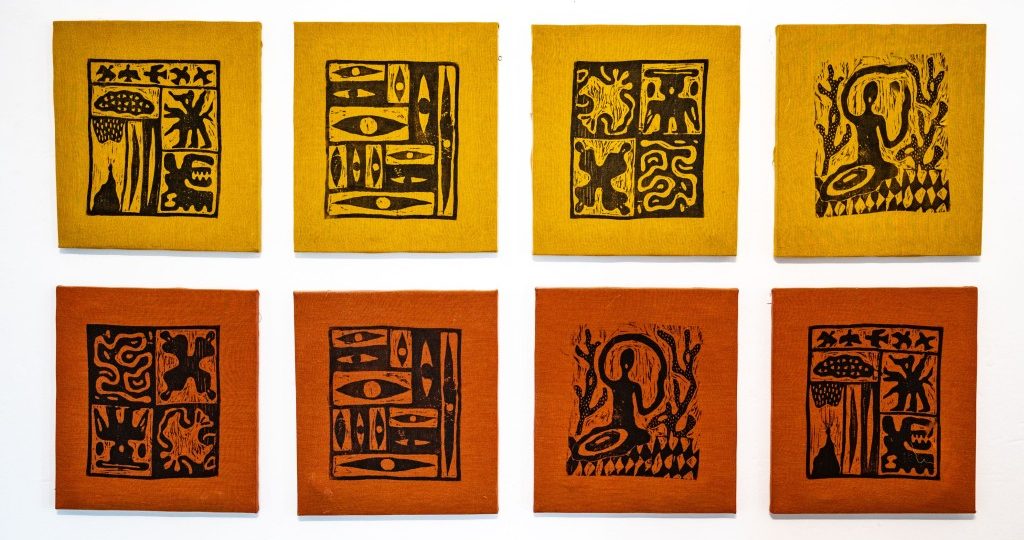

AÏKA : That’s nice, speaking of fabrics. I saw you work at Maison Aïssa Dione, and especially the one that you describe as maps, could you elaborate on what was the vision behind?

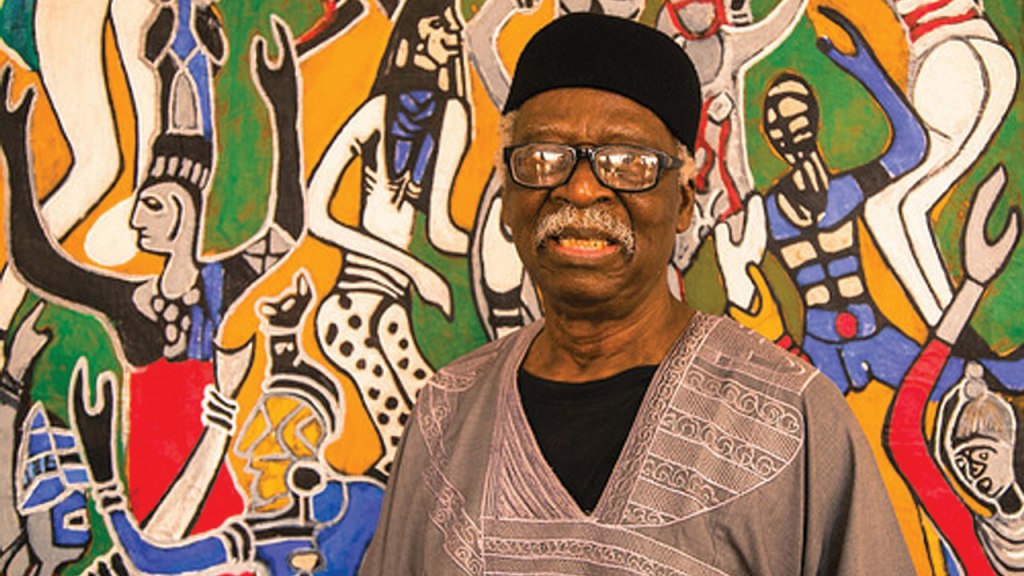

Yadichinma : I’m currently interested in the traditional crafts that have existed in African societies. I try to remain aware of this phenomenon, but it’s easy to overlook because the focus on arts is very Eurocentric. I heard about Picasso before Bruce Onobrakpeya, a Nigerian master artist. We’re often exposed to foreign artists before our own continent’s. Growing up with this education, I started feeling disconnected from my own space and society. So, I broadened my curiosity to what existed before and how I could translate it. Hence, this exhibition is titled “In a Language of My Own”.

I’m Igbo, from the eastern part of Nigeria, with a rich cultural heritage that’s documented but diffuse. I’m interested in the mythological and spiritual aspects of our cultural practices.

Textiles in many African cultures are a means of storytelling so naturally, I wanted to work with textiles when I arrived at Maison Aïssa Dione, especially given Aïssa’s expertise as a textile producer. The question of textile production in Africa is intriguing; it’s a common craft but fading. While we’ve always produced textiles, 80% seem to come from elsewhere.

For the maps I created, it’s me leading a kind of aerial survey of the land. I needed a map to navigate igbo history, so I studied Ala, the Igbo goddess of creativity, fertility, and earth. I built the maps finding symbols linked to Ala, inserting my own symbols and researching pre- colonial igbo architecture. I represented these ideas using embroidery on fabric. The maps act as a visual and spiritual guide, helping me intimately understand our origins.

AÏKA : That’s really cool, and very powerful what you’re saying. I’ve always had this vision of art as a tool to document, archive what happens in a space, a society. And I’ve always loved art because I find it’s also a means of transmission. In my opinion, art has given me insights into my culture, where my school education couldn’t. Is there a recurring theme in your various works?

Yadichinma : Yes, it’s something quite abstract. During my very first solo exhibition, the theme ‘of things to come’ emerged. I had this idea that I was a messenger of lost information passing through me. At that time, I wasn’t particularly interested in my cultural heritage; it was just me and the abstract symbols that came to mind. I placed them in spaces I called environments, and the idea was that I could summon my own images and then give them purpose by combining them in different configurations.

Because that’s the idea, if you put a line and a circle on a piece of paper, what message does that image convey? So, the recurring theme is, I suppose to discover the hidden relationship between things by placing them in different environments, recognizing that each object has an environment within itself. So, I’m always constructing a sort of sensation, a sort of room for every detail, whether it’s a line, a curve, or, inside, an actual figure. I place it within the context of a new space. I’m trying, I suppose, to develop its meaning in that space.

AÏKA : When you talk about your work, I can’t help but think of the surrealist movement.

Yadichinma : Exactly. I love it when that comes up, without me being super direct about it. I think the first body of works I discovered on my own that really touched me were surrealist works especially those of Salvador Dali. I enjoyed coming past just making representational work to developing my own images and imbuing them with my own meaning. That’s why you won’t see many portraits in my work. So, you rightly see a connection with the surrealist movement in my work, and also a lot of abstraction because I try to stimulate my imagination and think about how things could be different.

AÏKA : When you create a piece or a series of works for an exhibition, what is your goal? And what impact do you want your art to have on the audience?

Yadichinma : I think my main goal is to inspire wonder. So when people tell me, “I’m not sure what it is, but I feel like I know what it is” that’s exactly what I’m aiming for, a feeling of something strange but familiar. You don’t need to provide a definitive meaning, but there’s something very comforting about recognizing, feeling something, and saying to yourself that there’s a familiarity that has been created with the work in question. It’s in the same way science is able to define that everything is made of atoms, and that’s the singular truth we can feel. I want to be able to convey that singular truth, and for everyone to actively participate in the world I’ve created. There’s also this desire to document and archive society as it is, and also to remember where I come from. That’s why my work is now much more referential. There’s more research than before..

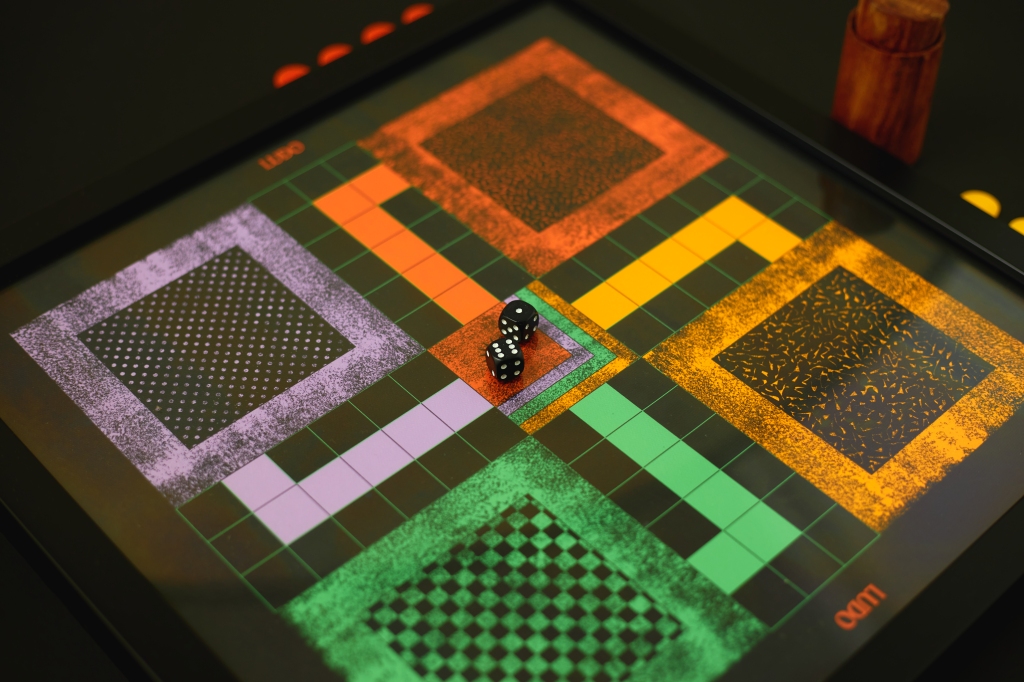

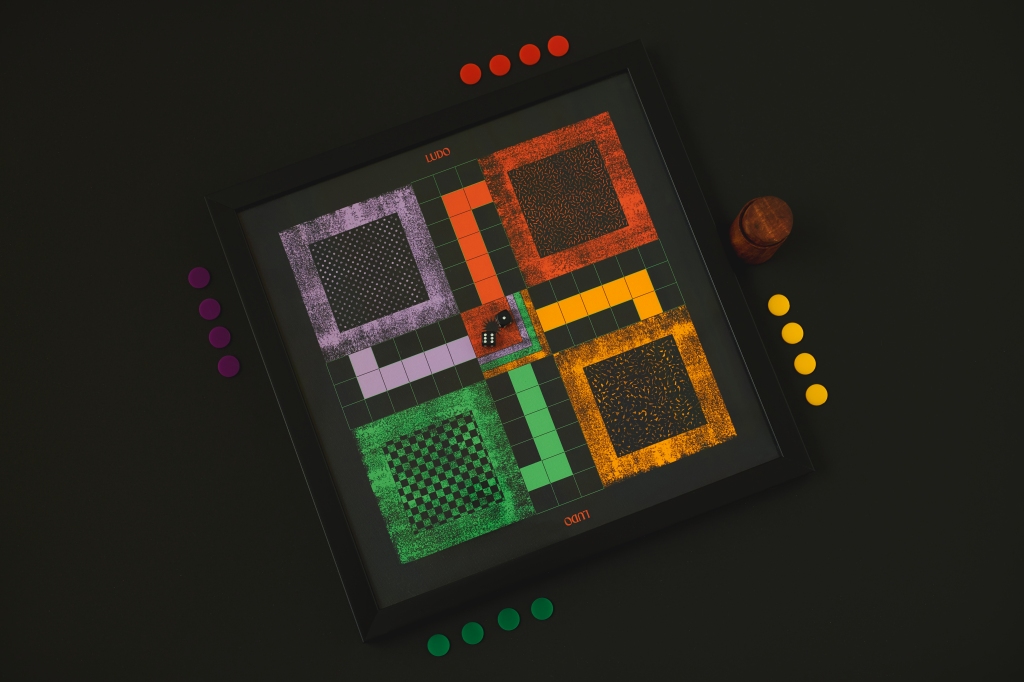

AÏKA : I noticed that you created a Ludo board game, 99% made in Nigeria. This creation caught my attention because when I was younger, I used to play Ludo, a game my parents played in their home countries. This game is part of my African cultural heritage, even though it wasn’t invented in Africa. So, I’m wondering how your culture or spirituality influences your work.

Yadichinma : I have always liked the idea that design and illustration translate into functionality, but especially into play. I love asking questions like, How can I create something that we can all play and interact with ? What story does this object connect us to ?

LudobyYadi is made in Nigeria because I wanted to prove that within our context, it is entirely possible to produce this kind of effort and work. Often, when you think of production, especially in third-world countries, many things are not accessible. There is not always electricity, but there is abundant craftsmanship. You have to extract resources very slowly and patiently, but it is possible, and these are the ideas that I am trying to promote by making objects here and involving local artisans.

AÏKA : Earlier, I spoke about how I perceive art as a means of documenting, archiving society. I greatly appreciate the work of great master photographers, such as Malick Sidibé, Mama Casset, or even Seydou Keïta, because when I was younger, as I explored my grandmother’s archives, I saw portrait photos of her, my mother, my uncles, and aunts, etc. And when I discovered the work of these photographers, I was pleasantly surprised because it resembled those old family photos. In your opinion, what is or what could be the impact of art, particularly on the African continent?

Yadichinma : In my view, the impact is enormous. Without being naive, I like to believe that this is exactly why you and I can be sitting here today. It gives meaning to life, it also gives a sense of anchoring, and knowing where one comes from really reinforces identity. Similarly, to popular media nowadays, the world of art and artistic production has been largely controlled by the West and by Europeans, and these people are storytellers, and they understand the idea and impact of narration, especially in the modern world. There are things you can impose through violence. But as soon as you have the power to tell your own stories and document your own stories, and to share them with the world, it becomes a way of validating what happened and that you were there. It’s no longer just like a mist floating in the air, but you can firmly hold onto it to say that these are the roots, and this is the story.

So, I really think it’s important to document, to archive. Art is also a beautiful way of thinking, of living in the world, and it opens your mind and helps you creatively navigate the space in which we live. We are born into systems where we are told that we must be a certain way, art gives us alternative outlets, to redefine what pleasure is, and what we are. We need that as human beings, particularly in Africa, we need this new way of being, to know that we also have access to this creative power, because it’s often something we forget.

We think we are powerless to change what already exists, but as soon as you familiarize yourself with your creative process, you understand that everything that exists was created by someone who simply said, “This is what I’m going to do today” and you can see what you are going to do today. That’s what I think is important for Africa and its relationship to art.

AÏKA : Indeed, for me, it’s truly about the power to redefine existing assumptions. Redefining one’s identity and knowing that there’s an alternative to what we’ve always been taught. That there’s a multitude of stories and we can identify with the ones we choose. It’s something I’m still trying to deconstruct today, and it’s difficult because I was born in France, my artistic education was in France, my professional experiences were in France. So, I have very Westernized interpretations of art. However, I feel particularly moved by the art produced on the continent and by the diasporas because I feel much more connected to it. Therefore, I try not to impose my artistic aspirations onto African art scenes. The last question I’d like to ask you to close this exchange is, what are your aspirations for the development of the art world in Africa?

Yadichinma : Personally, I really want to have the opportunity to establish creative communities that children especially can access, because I think that being young and exposed to creativity in a certain way really empowers you. I want the chance to inspire wonder because it’s a feeling that marks young people and they remember it for a long time. I’m a self taught artist, but between the ages of 20 and 22, I had the chance to frequent a community in Lagos called ‘Stranger’ founded by Yegwa Ukpo, it was a small japanese inspired cafe-boutique where I was really encouraged to make things. I had just started as an artist and being in that space and in contact with all the people who also frequented it brought me a lot. We formed a small community that shared things like films, art, books and much needed deep conversations about the world around us. I find that these kinds of spaces and communities are important, especially in Nigeria where there are few places like this where people can gather to sit together and think together.

Nice share!

Thank you

Good shout.